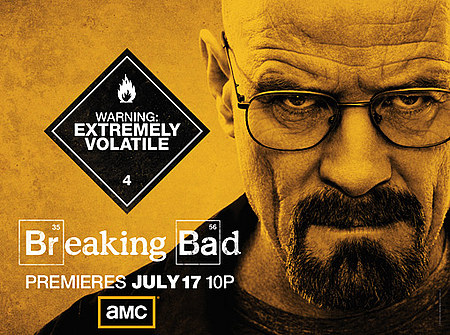

Heroic qualities are infrequently associated with the name Walter, which is old-fashioned and lacks charisma and dynamism. It’s more likely the name of somebody who works as a high school chemistry teacher than somebody who, say, deals drugs.  These two disparate enterprises, however, come together in the form of Breaking Bad‘s Walter White (Brian Cranston), a seemingly humdrum high school chemistry teacher who lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Like everybody, he contains multitudes, and beneath his unimaginative, follow-the-rules exterior is a man with a pregnant wife and a teenage son afflicted with cerebral palsy. As if he were insufficiently burdened by the vicissitudes of life, Walter is then diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, which has a weirdly clarifying effect on the man.

These two disparate enterprises, however, come together in the form of Breaking Bad‘s Walter White (Brian Cranston), a seemingly humdrum high school chemistry teacher who lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Like everybody, he contains multitudes, and beneath his unimaginative, follow-the-rules exterior is a man with a pregnant wife and a teenage son afflicted with cerebral palsy. As if he were insufficiently burdened by the vicissitudes of life, Walter is then diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, which has a weirdly clarifying effect on the man.

Realizing that his already vulnerable family will be crippled by medical debts after his death, he decides to abandon the straight and narrow and use his knowledge of chemistry to not only teach his students, but to sell them drugs. Enlisting the help of an ex-student, Walter begins to manufacture and sell methamphetamine. Of course, given the illegality and morally dubious nature of this endeavor, he must keep it secret from his family, thus ratcheting up the tensions in his dwindling life.

Breaking Bad, which is winding down its second season, has been a critical darling from its inception. There are all sorts of things to like about the show, including an unstinting intelligence and a commitment to acting that’s persuasive and compelling. The production team manages to take a somewhat fantastical conceit and keep it authentically rooted in the middle-class culture, and in spite of the heavy circumstances of its principle character, there’s a buoyancy and wit to Breaking Bad that actually, in a complex way, makes it an optimistic and hopeful story. In a very raw and basic way, what Walter is doing, in opposition to a cruel and arbitrary world, makes perfect psychological sense. He has chosen to fight, if not exactly for his life, then for the continued survival of his family, and in doing so he’s amplifying the most basic tenets of heroism.

Breaking Bad is at its most entertaining when it’s taking us into the drug culture of the street. Our entry point to this world is Walter’s partner in the meth business, Jesse (Aaron Paul). A thin white boy who cops the patois of gangster culture, Jesse is a likeable fuck-up. However, he’s never played strictly for laughs, and like all the characters on the series, he’s allowed sufficient latitude to be all sorts of different things at once.

The show’s depictions of street life are jazzy and improvisational; they’ve got a real visual brio about them, projecting both velocity and abandon. On one episode, we follow a cadre of street dealers as they ply their trade in the derelict corners of the city. A montage offers us a glimpse of stoned piggyback fights, stray dogs, sunken eyes, and forgotten stashes from unanticipated angles before ending with the image of a scabby junkie, cackling senselessly, as she and her partner rob a dealer.

Another strength is the way the subplots, including one involving a DEA agent named Hank who’s investigating the new meth kingpin in his jurisdiction, enrich the central narrative of each episode. Stocky and bald, Hank resembles a torpedo. As American as the 1950s, he’s the sort of macho configuration that makes you feel like a sissy for never having fired a gun, and whom, infuriatingly, your son adores. He also happens to be Walter’s brother-in-law.

Although this conveniently structured game of cat and mouse could have been played out with ham-handed simplicity, it’s not. Both Walter and Hank are ambiguous characters, driven by the nuances and contradictions that are attendant to adult lives. Hank, trying to conceal the panic attacks he suffers due to the warrior culture he inhabits, and Walter, seeking to conceal his cut-throat gangster identity from a world that sees him enfeebled and emasculated, have much in common. Hank has no idea of Walter’s double life, but what keeps their relationship interesting is not just that tension, but the honest affection they have for one another in spite of their outward differences.

The scenes in which Walter receives chemotherapy for his cancer are rendered with a tender, almost beautiful attention. Shot in extreme close-up, we see chemicals flow mysteriously through a catheter and into his blood stream. Walter’s face, pale and sunken, fills the screen, and in it we can see his hope that this chemical agent will alter the composition of his body and eliminate the cancer growing inside. Through some magical trick of alchemy, some people fall ill while others prosper, some finding a cure, while others perish. Breaking Bad sees something almost holy in the chemistry of the body and the brain, offering us a sweeping and complex look of the intricate forces that guide the trajectory of our lives.