Yesterday while walking the dog I came upon a very old woman sitting on the landscaped ledge of some property.

Appearing listless, she perked up when we approached and became animated at the sight of Heidi. I steered the dog toward her and the old woman nuzzled her ears and complimented her coat. We fell into the type of brief, friendly conversation you might imagine, “I am 89,” the woman stated flatly. “At 90, no more,” and she made a dismissive gesture, suggesting that would be the end. I asked if there was anything I could do to help her, “No, no. Thank you. I am old. I get tired so I sit to rest. You and nice dog go, I thank you,” and then she fanned us away with short, broken fingers.

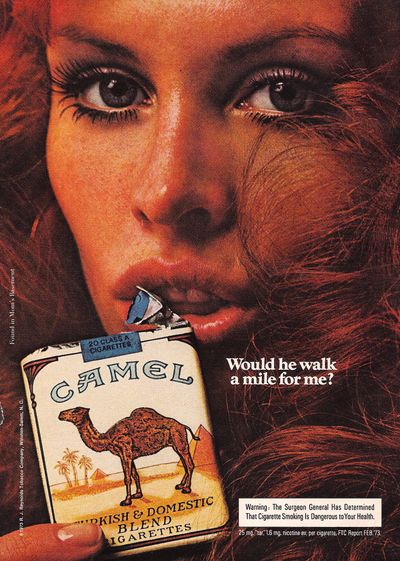

A tall man stepped out of the recovery house at the end of the street. He was moving quickly, with anger in each step, and as soon as he hit the street he dug into his pocket, grabbed his smokes and lit one. On his calves were these horrible blotches that looked like a furious rash that was just now coming to order. On the steps above, leaning against the railing and watching him were three men. All of them looked uncomfortable in their scratchy shirts and ties, each one smoking and emitting a sense of deprivation and hostility that was palpable, even on the street beneath.

On Bloor we had the green light to cross but our passage was blocked by a luxury Mercedes that was situated directly in the middle of the pedestrian crosswalk. There was ample room for it to get out of the way and go either forward or back, but the driver at the wheel was distracted. She was texting, and as she was doing so she was smiling—maybe a good idea, the reception of happy news, calming plans. Normally I’d be touched by this glimpse into the small optimisms of a life, but by virtue of the hierarchy her car was designed to imply, all I could see was the sense of blind entitlement money bestows upon certain types of people.

We then popped into Queen Video to return a few rentals. The woman behind the counter, normally an enemy who refused to make eye contact or communicate beyond the rudimentary necessities of the job, was different. Typically sullen and angry, she was open and affable. She had abandoned her usual attire of severe glasses and a Death Metal Tee, and now in contacts she wore a heartbreakingly bad shade of eye shadow and the sort of top that an aunt from Scotland might send to you as a gift. For the first time in the five years that I have been going there, she wanted to give Heidi a treat. She spoke easily, talking of her own dog and a conversation developed between us and several other customers, each one of us saying things that made the others laugh, and whatever love had found the clerk was now beginning to spread.